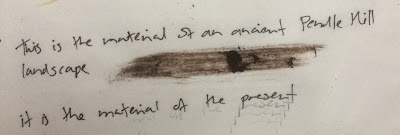

Kerry Morrison – socio-ecological artist

As part of the peat restoration work on Pendle Hill Summit, throughout 2018 and 2019 artist Kerry Morrison will be researching and

developing creative ways to highlight the value of peat and engage local

communities in deepening understanding around peat restoration.

Kerry is particularly interested in the parallels that can be drawn between the process of peat restoration and textiles: the knitting of the landscape, the repairing and stitching together of the hill. A performance involving local people and groups in early 2019, finishing off the restoration works, will further explore these links.

This research will inform a socially engaged interdisciplinary art and ecology project in 2019. There will also be two Peat Art and Ecology Conferences that join up this work with other Landscape Partnerships that have involved artists nationally, for example, Galloway Glens, working with artist Kate Foster.

Kerry is particularly interested in the parallels that can be drawn between the process of peat restoration and textiles: the knitting of the landscape, the repairing and stitching together of the hill. A performance involving local people and groups in early 2019, finishing off the restoration works, will further explore these links.

This research will inform a socially engaged interdisciplinary art and ecology project in 2019. There will also be two Peat Art and Ecology Conferences that join up this work with other Landscape Partnerships that have involved artists nationally, for example, Galloway Glens, working with artist Kate Foster.

PEAT

A blanket

over the hill

Locking in

carbon

Supporting

wildlife

Holding in

water

PEAT

In a broad

brush stroke

peat is a

type of soil

a covering

of earth

formed over

decades and centuries and millennia

from

decaying plant life

in

particular, sphagnum moss species

strands

clumped together

forming deep pile cushions

(Some

Sphagnum Species, drawings by Kate Foster 2015)

(photo by Kate Foster)

There are a

number of things that make peat particularly special and massively important:

- As the plant material breaks down into peat it locks in the carbon dioxide stored in the plant matter. Peat landscape are incredible carbon sinks

- Peat and the moss vegetation it supports hold water. They swell and shrink with wetting and drying. Like sponges, mosses and peat soak up and store rain water, helping to prevent storm water run off and flooding

- Peat landscapes support wildlife. Peat, as a very specific type of soil supports a specific ecosystem. The acid loving vegetation that grows on it, the insects that feed from that vegetation and the birds and mammals that feed on them are all supported by peat - and some are unique to upland peat landscapes.

Bringing all

this back to Pendle Hill…

the geology

that is Pendle Hill is covered in peat formed over thousands of years

a blanket if

you like

but sadly, this

blanket’s quilt of vegetation is, in parts, missing

the peat is

bare

vulnerable

to erosion

nothing

holding it in its place

nothing

growing that will decay and form more peat

with the wind

and the rain

and

footsteps of people and animals

the peat a

top o Pendle Hill is washing, blowing and wearing away

this erosion

is happening at a rapid pace

but it can

be halted and the hill’s landscape can be restored

With thanks

to Heritage

Lottery Funding

The Pendle

Hill Landscape Partnership is currently restoring Pendle hill’s peat landscape

and I

as an artist

commissioned by In-Situ

as part of The Gatherings

strand of the Pendle Hill Partnership

will be

communicating the process of restoration in novel ways

spreading

the importance of peat

the

importance of protecting the peat

at the top of

Pendle Hill

to towns and

villages and communities

around

Pendle Hill

many ideas are flowing

the performative patterns of

restoration

choreographed in the landscape

stitching the landscape together

weaving metaphors

spinning the connectivity

and interconnectivity

at the top of the Hill

and around

the Hill

As an artist

exploring

Pendle’s peat

It’s importance

It’s complexities

Why it is necessary to restore the peat

landscape on top of the hill

The process of how it is being restored

will, over the

next 12 months, be expressed through imaginative and engaging creative

processes…